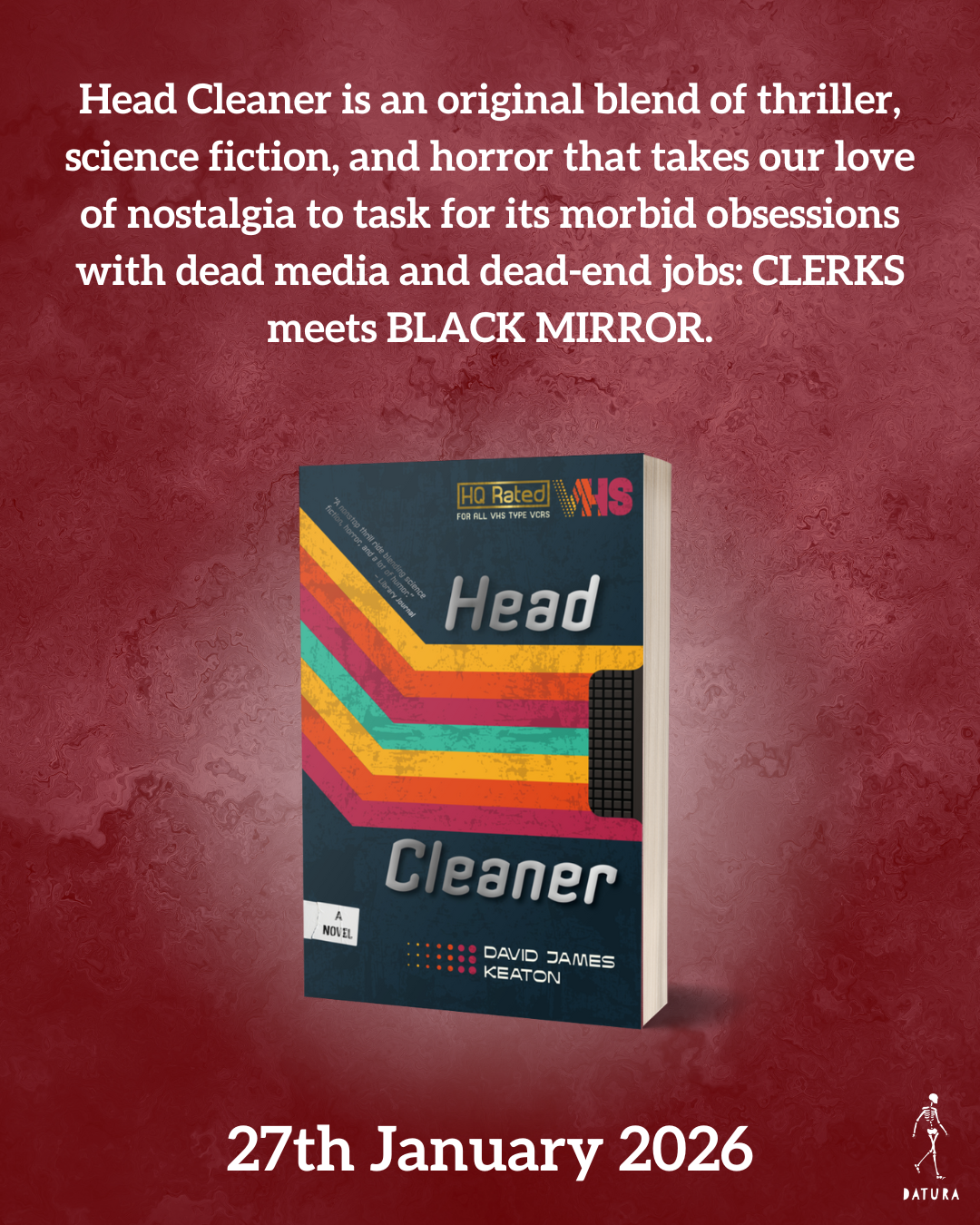

The final cover for David James Keaton’s HEAD CLEANER is here! 📼😱

Check out the new cover for HEAD CLEANER, the wholly original sci-fi/thrilller/horror mash up by award-winning author David James Keaton! 📼😱 ABOUT THE

Happy New Year crime lovers! Today on the Datura blog, we have a very special guest post from Alice McIlroy, the author of The Glass Woman, which is out today! Read on to learn more on her thoughts on writing, therapy, and the use of A.I. technology for both.

Could A.I. be your future therapist? “We can get through this together,” says Woebot, an A.I. chatbot and mental health “ally” app. Togetherness seems to be a key tenet of modern therapeutic practice, but how healing can it be when your “ally” is, at best, an A.I. bot emulating empathy? There are already a staggering number of mental health apps available offering A.I. chatbots in what some have called a social-psychological “experiment”. Can A.I. replicate the human aspect of a client-therapist relationship, and, ethically, should it?

Who is responsible when it goes wrong?

I don’t have the answers, but this human-A.I. therapeutic relationship is one of the subjects explored in my debut novel, The Glass Woman. Out today, The Glass Woman is a psychological thriller where a scientist, Iris, wakes up to be told she is the first to trial a pioneering A.I. brain implant, Ariel. Iris is told Ariel is an internal A.I. therapist programmed to help her process trauma. It is speculative fiction about where our relationship with A.I. could lead us, but mental health chatbots are already very much in existence today. Given real-life therapy is often unaffordable, and demand outweighs therapists, a readily available option is perhaps appealing. But when therapy is based on the strength of relationship and connection between therapist and client, can A.I. really help, and, ethically, should the use of A.I. enter such a sensitive domain as mental health? Should we be outsourcing a role that deals with the complexity of the human psyche, and defers judgment to algorithms trained on data from the internet, even if an A.I. therapist is highly effective at emulating the therapeutic relationship?

Computer scientist Joseph Weizenbaum’s first conversational computer programme, ELIZA, was an early chatbot in the 1960s based on psychotherapy. So strong was the illusion of ELIZA’s understanding that Weizenbaum wrote that some subjects had been “very hard to convince that ELIZA (with its present script) is not human.” Weizenbaum found this “ELIZA effect” troubling, cautioning against the use of A.I. for human functions, concluding that “no computer, can be made to confront genuine human problems in human terms.” Not only that, he suggested that no human could fully understand another human, so complex is the human psyche.

Which is why I’d like to talk about another form of therapy: writing. We live in a culture where often our first response to a problem is to turn to therapy for the solution. One potential challenge with therapy (whether A.I. or human) is bias – or for human therapists, impartiality. A.I. might be emotionally impartial (or rather, only able to simulate emotion), but it inherits the bias of its training data. Whereas, even the best human therapists will unavoidably bring some of their own emotional history to the session. The therapist, the recipient, will invariably have their own preconceived ideas and first impressions about you, the client.

I began writing The Glass Woman in 2017 and between then and now, I became very ill. During a year-long period of illness, I wrote as therapy. If you write as therapy, the content you are writing is not (at least not necessarily) intended for a particular recipient, and there is a freedom inherent in that. With therapy or counselling, there is a specific recipient (the therapist) with preconceived ideas and so the person seeking therapy is likely to filter some of what they say in accordance with their perception of how the listener may react to and receive the information. Writing is as a result, in some ways, a freer and perhaps more liberating form of expression. What is more, it has been well-documented that expressive writing can help people to heal from trauma. In addition to this, with fiction, there are the parameters of fiction itself – everyone reading it knows these are fictitious events and people, which offers the writer greater freedom to explore topics and issues that are difficult to talk about in relation to real life; fiction can act as a shelter for the writer’s exploration of themes and events by proxy.

So, if you’re considering a digital therapist, perhaps try writing as a purer, more unadulterated form of therapy. You could also try reading The Glass Woman to discover how an extreme form of A.I. therapy works out for protagonist Iris.

The Glass Woman by Alice McIlroy

Black Mirror meets Before I Go to Sleep by way of Severance.

If you could delete all the hurt and pain from your life… would you? Even if you weren’t sure what would be left?

Pioneering scientist Iris Henderson awakes in a hospital bed with no memories. She is told that she is the first test-subject for an experimental therapy, placing a piece of AI technology into her brain. She is also told that she volunteered for it. But without her memories, Iris doesn’t know what the therapy is or why she would ever choose it.

Everyone warns her to leave it alone, but Iris doesn’t know who to trust. As she scratches beneath the surface of her seemingly happy marriage and successful career, a catastrophic chain of events is set in motion, and secrets will be revealed that have the capacity to destroy her whole life.

Alice McIlroy’s writing has been longlisted for the Stylist Prize for Feminist Fiction and Grindstone International Novel Prize. Her debut novel, The Glass Woman, was published on 2nd January 2024 by Datura/Angry Robot Books. It can be ordered here.

She can be found on Twitter @alice_mcilroy and Instagram @alicemcilroy_author.

Check out the new cover for HEAD CLEANER, the wholly original sci-fi/thrilller/horror mash up by award-winning author David James Keaton! 📼😱 ABOUT THE

We are announcing and revealing the final cover for WHEN WE WERE EVIL, out January 13th 2026! Prepare for a dark and gripping thriller set

We are delighted to formally announce and reveal the final cover for Blood Rival, the addictive, new thriller from critically-acclaimed author Jake Arnott! For fans

Check out the new cover for HEAD CLEANER, the wholly original sci-fi/thrilller/horror mash up by award-winning author David James Keaton! 📼😱 ABOUT THE

We are announcing and revealing the final cover for WHEN WE WERE EVIL, out January 13th 2026! Prepare for a dark and gripping thriller set

We are delighted to formally announce and reveal the final cover for Blood Rival, the addictive, new thriller from critically-acclaimed author Jake Arnott! For fans